Medically reviewed by Dr. Lee Ann Richter

When 78-year-old Ann Hoffman experienced a fall in November 2018, she drove herself to the emergency room. It was at the hospital that she noticed an increased need to urinate and found blood in her underpants. For a postmenopausal woman, this seemed strange to her.

“I asked the doctors if it was related to the fall,” she told HealthyWomen in a recent interview, “but they said it wasn’t.” Hoffman was then given a urine test that showed she was positive for a urinary tract infection, or UTI. She was prescribed an antibiotic and sent home.

Some time passed and Hoffman once again experienced the same symptoms. This time, she went to see a urologist. While a UTI was suspected, the urologist decided to look more closely at her symptoms. Hoffman was told she may have bladder cancer, which develops when cancer cells begin to grow in the bladder.

A cystoscopy, a procedure where a small tube is inserted into the bladder to allow a healthcare provider (HCP) to take a look, with a bladder biopsy confirmed that Hoffman did indeed have urothelial carcinoma. Also called urothelial bladder cancer, or UBC, this most common form of bladder cancer begins in the urothelial cells and is a cancer of the lining of the urinary system. Invasive urothelial or transitional cell cancer can not only be found in the bladder, but in the kidneys, ureters and urethra.

Like the symptoms Hoffman experienced, blood in your urine and frequent urination are two of the main signs of UBC. Other symptoms can include painful urination and pelvic or back pain. In Hoffman’s case, her cancer was noninvasive, which means it hadn’t grown into the deeper layers of the bladder. Invasive UBC, when it has grown into the muscles, is harder to treat and can often spread more quickly.

Hoffman received six weeks of bacillus Calmette-Guerin or BCG treatment, an immunotherapy that can help keep UBC from progressing or coming back. When she completed her treatment, further testing showed that she was cancer-free.

Whom does UBC impact?

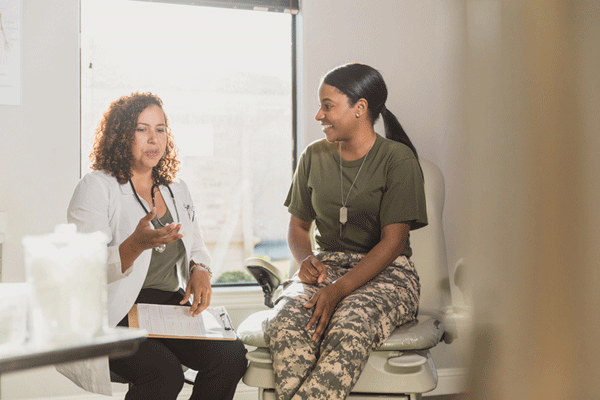

While Hoffman was lucky to catch her UBC early, diagnosis can often be delayed in women because it can be mistaken for common UTIs or postmenopausal bleeding. According to Dr. Lee Ann Richter, a urologist who specializes in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery, women who have blood in their urine in the absence of an infection or persistent blood in the urine should be seen by a urologist for further testing.

This can help rule out or lead to an early diagnosis of UBC, which approximately 19,000 women are diagnosed with each year. Although it’s not one of the first cancers that may come to mind for women, there are approximately 5,000 women who die from UBC annually, she noted. This is why being aware of warning signs is so important.

While the disease is more common for men, who have a 1 in 27 chance of developing it during their lifetime (compared to 1 in 89 women), some believe women may face a worse prognosis. There is some evidence that women are generally diagnosed with more advanced stages of UBC. The female sex has also been associated with more aggressive tumor characteristics, which leads to more unfavorable outcomes.

Overall, the cancer mostly affects older populations. In fact, 90% of people with bladder cancer are older than 55, while the average age of diagnosis is 73. Younger people do present with the disease as well, Richter said, but it’s less common.

She also explained that race can play a role in one’s risk level for UBC development. White individuals are approximately two times as likely to be diagnosed with bladder cancer as Black and Hispanic individuals, Richter noted. Asian Americans and American Indians, she added, have slightly lower rates of bladder cancer as well, for reasons that remain unknown.

How to lower risk factors for UBC

There are a number of other risk factors that can impact potential development of UBC. However, women can mitigate many of these risks with lifestyle changes. “About 50% of bladder cancers are attributed to smoking,” Richter said. “The most important thing women can do to reduce their risk of bladder cancer is to avoid smoking.”

She also notes that working in industries that use certain organic chemicals, such as rubber, leather, printing or painting industries, can expose women to organic chemicals that may increase the risk for bladder cancer.

Yet, there are steps women who work in these industries can take to better protect themselves. “They want to do their best to avoid exposure to these chemicals by following good work safety practices,” Richter said. “They should also be having yearly checkups with their primary care physician.”

Annual physicals, she explains, are crucial because they often involve a urinalysis that can check for blood in the urine, a telltale sign of UBC. While some risk factors, like chronic irritation and multiple UTIs are more challenging to avoid, leading a healthy lifestyle can go a long way in keeping risk levels lower for UBC.

It can be tempting to self-diagnose a change in urinary symptoms as a UTI, especially for women, who are prone to developing the infections. However, Richter cautions against doing so. Women who have concerns about blood in urine, frequent or painful urination or pelvic pain should always seek evaluation with a urologist. UBC is taken seriously, she explains, and most urologists will take necessary steps to rule out the disease or investigate further if needed.

Thanks in part to early diagnosis, Hoffman is now cancer-free.

“If you have any of these symptoms [like I did], go to a urologist,” Hoffman said, explaining that she feels almost back to normal. “Don’t just stop at [assuming] it’s a UTI.”