As told to Erica Rimlinger

As part of a military family, service is in my DNA. I knew from high school that I would serve, and the Navy paid for my college with an NROTC scholarship. My college graduation was followed two days later by my marriage. And two weeks after that my husband and I were off to Virginia where I reported to my first duty station. I was assigned to a destroyer, and my job was to learn to be a Naval officer and lead the anti-submarine warfare division. A little over a year into my tour, I deployed for seven months to the Persian Gulf.

When my deployment ended, I took a desk job, and my husband and I decided it was time to start trying to have a baby. Unfortunately, after I stopped taking the birth control pill, my period wasn’t regular anymore. I went six months without a regular period — and even more notable, without getting pregnant. My primary care doctor was not alarmed. Yes, it was, they admitted, a little strange for a 23-year-old woman to have fertility problems, but they wanted to wait a full year before I started infertility treatments.

But I had an app, and this app was collecting data that showed me and — perhaps more importantly at the time — my doctor that something was not right with my cycle. Faced with more than six months of data, my doctor prescribed clomiphene, a medication that helps you ovulate, which gave me ferocious hot flashes and no positive pregnancy tests.

Trying to conceive went from fun to, well, trying. I struggled with stress, anxiety and my sense of self as a woman because I was unable to do what was “supposed to” just happen naturally. Every ounce of hope carried us another foot up the steep roller coaster track until we reached the top and a negative pregnancy test sent us into yet another freefall of disappointment. We’d try again, with a little more scar tissue over our hearts and hopes. I had the added frustration of knowing that my cycle was signaling that something was wrong — and having the data to prove it.

Finally, after a year, I was referred to a fertility specialist, a reproductive endocrinologist. I was grateful the Navy covered this care, but it took a little while to get an appointment after the referral. Time was ticking by: At some point, I’d be going back to sea and would lose my chance to start my family.

The reproductive endocrinologist had a bedside manner that bordered on rudeness. “You’re 24. Why am I treating you?” he asked me repeatedly. But during my full workup — which included blood tests and ultrasounds — we found there was a reason I wasn’t getting pregnant. I had polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and I wasn’t ovulating. I started taking medication for PCOS, but it didn’t help. At that point, I qualified for a procedure called intrauterine insemination (IUI), where my husband’s sperm would be placed directly in my uterus in hopes of getting me pregnant.

I lived in Virginia at the time and started making the regular commute to the Navy’s Portsmouth medical center in Hampton Roads. Fortunately, I had a boss who allowed me to take the time off for all the appointments involved. I took clomiphene and went to multiple ultrasound appointments to make sure the follicles in my ovaries were growing. If they weren’t ready, we’d have to keep returning until they were.

Meanwhile, my husband produced his sperm sample, which I received through what we call the “turkey baster method.” My husband would give me my shots in the upper butt, which neither of us enjoyed. Because I was on active duty, these treatments were covered by the Navy. The only part of the process we paid out of pocket for was the preparation of the samples my husband gave, since he was a civilian.

The second time worked. I had a feeling it worked when it happened, and this instinct was confirmed a week after the procedure when I opened yet another pack of pregnancy tests and got my first pink line. I was ecstatic as I snapped a photo of the thin pink line that told us our dream of becoming parents was moving forward.

Technically, my pregnancy was high risk, but for me personally, pregnancy was easy and enjoyable until the middle of my third trimester. Somewhere around the 32nd week, I noticed I was getting puffy. Like many of my compatriots in the Navy, I pride myself on the ability to push through discomfort. But when you’re pregnant, pushing through can be risky.

I started having Braxton Hicks contractions at 34 weeks while driving home from work. The traffic police actually stopped me for speeding. Once they realized I was having contractions they called an ambulance to take me to the local hospital — but they still gave me a speeding ticket. (To this day, I think, “Really?”) There, my bloodwork showed I had protein levels so high the staff ran the test twice because they thought the lab made a mistake. I was told to follow up with my OB-GYN, who diagnosed me the following week with preeclampsia (high blood pressure that develops during pregnancy) and told me I wasn’t leaving the hospital until I had the baby.

I gave birth at 35 weeks and watched my baby get whisked into the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for apnea because of the preeclampsia medication. They eventually took my baby to the NICU at a larger hospital for more care. I was finally able to hold my child for the first time 48 hours after I got discharged. We were able to go home after two weeks in the hospital, a family of three at last.

I believe our family would have started much later if I’d not advocated for myself with my doctor. I knew my body, and I had the data from my fertility app to back up my feeling that something was not right.

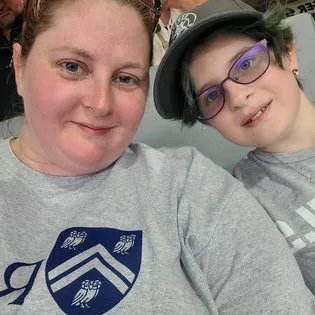

Now, as a mom to a 12-year-old, I hope my story helps other women in the military understand how important it is to be an active participant in their care. And I recommend all women listen to their bodies and trust their instincts.

Have a Real Women, Real Stories of your own you want to share? Let us know.

Our Real Women, Real Stories are the authentic experiences of real-life women. The views, opinions and experiences shared in these stories are not endorsed by HealthyWomen and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HealthyWomen.