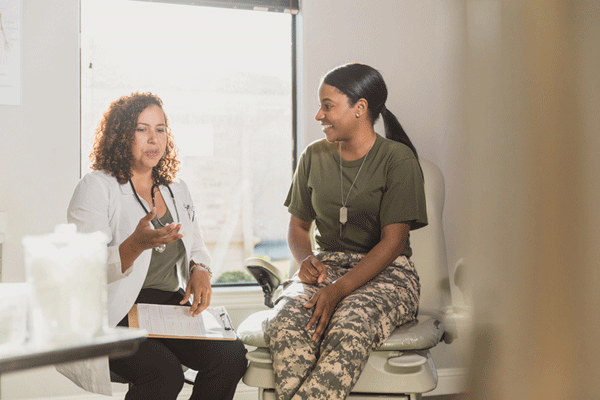

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are any infection of the urinary system, which is made up of the bladder, urethra, ureters and kidneys. They range in severity from simply annoying and uncomfortable to painful and potentially dangerous — and women and people with female biology in the military are more at risk to develop them, said Maj. Melody Nolan, a gynecologist with the U.S. Army.

While very common among women and treatable with antibiotics, UTIs can lead to kidney damage and sepsis if not treated.

People with female biology experience UTIs more often than men, and being in the military puts them at greater risk because they’re often in situations where maintaining hygiene can be challenging, Nolan said. Those situations include attending flight training, being on long flights, serving on a cramped naval platform or working in rugged environments.

Why are women in the military more at risk for UTIs?

A 2020 survey by the U.S. Army found that one in five of active-duty servicewomen had developed a UTI while deployed. Of those, approximately two out of three said the infection interfered with their performance and job duties.

The Army has attributed the increased risk of UTIs and other infections to a lack of privacy and clean facilities, such as showers, laundry services, toilets and handwashing stations. “Often there are only port-a-potties or other non-flush toilets available, and they are located a few hundred meters or farther from the training site,” Nolan said. “They may not be easily accessible, and they may not be clean.”

Nolan said another problem is that service members tend to not drink much water while in the field, in order to go long periods without using the bathroom. Holding in urine can cause bacteria buildup, leading to infections. Nolan also said that service members may not want to use the bathroom because they’re avoiding the inconvenience of removing their heavy, bulky gear, or because they have a mission that can’t be interrupted for safety reasons.

The lack of access to specialized healthcare also creates problems, according to Nolan. In a deployed environment, a service member’s only medical care might be limited to their medic or corpsman.

How can servicewomen prevent UTIs?

Educating service members with female biology about UTI symptoms and teaching them how to reduce the risks of infection can help prevent problems.

Nolan suggested that service members with female biology wash their hands before and after using the toilet and changing any menstrual products. When possible, they should avoid holding in urine and empty their bladder as soon as the urge occurs. They should also drink plenty of fluids, preferably water, to flush bacteria out of the urinary system.

These tips are published on cards that are issued to junior soldiers, Nolan said, but she admitted that they’re not always achievable. To lower the risk of infection during deployments or field exercises, Nolan recommended using hand sanitizer or unscented baby wipes to try to stay clean, and to wear underwear made of a breathable fabric, like cotton.

In cases where service members with female biology lack privacy or aren’t able to access a toilet, they can use a female urinary diversion device, known as a FUDD. The Army started issuing FUDDs to service members with female biology in 2013 with their military equipment. The devices allow them to stand while urinating.

“This can be really beneficial,” Nolan said. “[They] don’t have to remove military gear or undress, and [FUDDs] don’t need as much privacy to use.”

Nolan said that FUDDs are particularly helpful in military convoys. Service members with female biology can stand next to a stopped vehicle and use the device there. Going somewhere else to use the bathroom would be unsafe because of the risks of IEDs and other hazards.

Soldiers should wrap FUDDs in plastic bags in their pockets and rinse them with clean water and soap when they can.

What happens when prevention fails?

The signs of a UTI include burning or pain while urinating; a strong urge to urinate that doesn’t go away; pelvic pain, especially around the area of the pubic bone; and urine that looks cloudy or smells strongly. Urine can also appear pink, red or cola-colored — a sign of blood in the urinary tract.

“They often appear suddenly, and can worsen quickly if not identified and treated,” Nolan said.

The Army encourages service members with female biology to immediately seek out a medical provider at their duty stations if they notice symptoms of a UTI, saying that it’s important for self-care.

Nolan believes there is sometimes hesitance among servicewomen to report infections.

“I don’t think there is hesitancy to report symptoms in the garrison, where women have access to their healthcare facilities,” Nolan said. “I do think there probably is [hesitancy] in the field, or if they are not located near an experienced healthcare provider while deployed in combat or an austere environment. It can be embarrassing to bring it up.”

Simple UTIs can be treated with antibiotics. Women’s overall health, as well as the type of bacteria found in their urine, determines which medicine to use, and for how long. Symptoms typically go away within a few days of starting treatment in uncomplicated cases.

Complex UTIs occur when bacteria ascends into a patient’s ureters, Nolan said. That’s when patients can develop fevers, kidney pain, nausea and vomiting. In those cases, the person suffering from the infection should be hospitalized and receive antibiotics through an IV, she said.

When service members with female biology experience frequent infections, they may be prescribed low-dose antibiotics that they take over a period of months.

As with most avoidable medical conditions, rather than relying on treatment, it’s best to do everything you can to prevent a UTI in the first place.