When Tracey Kelly lost 70 pounds over a six-month period, she told everyone the low carbohydrate diet she was following was the best weight-loss program she’d ever tried. But even after she went off the diet and started eating fast food and drinking beer, she kept losing weight. When she wound up in the emergency room with histoplasmosis in 2002, she learned the real cause: She had full-blown AIDS.

“I’m an overachiever,” Kelly said. “I skipped right over the HIV part.”

Kelly’s ex-husband, who was bisexual, had died of AIDS in 1992. AIDS, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, is the disease caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a sexually transmitted infection that interferes with the body’s immune system.

When her husband passed away, Kelly didn’t understand her own risks for getting AIDS. She thought it was a gay man’s disease — not something women could get.

Now 58, Kelly is one of the 379,000 Americans over 55 living with HIV. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that HIV infection rates among older men declined between 2014 and 2018, but haven’t budged among older women. In 2018, people over 50 represented more than half of the people living with HIV in the U.S., almost a third of whom were women.

Thanks to treatment advances, people are also living longer with HIV than they used to. That also means many face barriers to care related to aging, such as low awareness and multiple chronic conditions, along with costs and stigma that others with HIV/AIDS also face.

Lack of awareness

The most basic barrier older people face is lack of awareness of their HIV risk. According to the National Institutes of Health, less than 9% of older people reported getting tested for HIV in the previous year — fewer than any other group. Older people are also more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage HIV and to start treatment later, putting them at risk for worse health outcomes.

“Unfortunately, there still have been no real targeted efforts for prevention or even for testing. A lot of people don’t even know when they should get tested,” said India Bowman, an assistant research scientist for PatientsLikeMe, whose public health work focuses on treatment barriers for people with HIV.

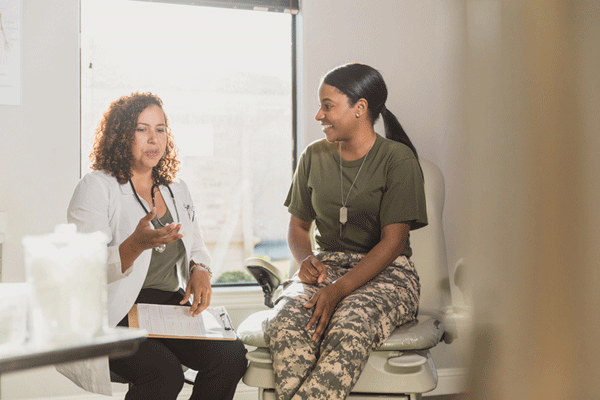

Awareness campaigns may also be missing the mark for older women, who rarely see themselves in educational material. Bowman said that most HIV education campaigns are targeted at men who have sex with other men, who still make up the majority of people with HIV.

But the lack of representation of older women runs deeper than just whose photograph is on a pamphlet. One of the biggest barriers is that treatment, research and prevention measures are not targeted toward women, according to Bowman.

Complex needs

Managing a complex condition such as HIV/AIDS can be challenging enough, but many older women with HIV have multiple health conditions, making it harder to access and manage all the care they need. Older women with HIV are particularly vulnerable to heart disease, diabetes, cancer, depression, neurological disorders, osteoporosis and kidney and liver disease.

Juggling providers, appointments, medications and treatment plans for multiple complex diseases can also create additional barriers to care. And this is even harder for people living with other challenges, such as mental health and substance use disorders, poverty and unstable housing.

More than half the people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States qualify for the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, a federal program that funds medical care, support services and medications for low-income people with HIV.

High-cost and hard-to-access medications

Treating HIV/AIDS can be complex and expensive, which creates even further barriers to care.

Kelly was lucky that her job-based health insurance initially covered her medications, which can cost thousands of dollars each month, but Kaiser Family Foundation data suggest that her coverage was unusual. In 2018, one person in 10 (11%) with HIV/AIDS were uninsured, comparable to the general population, but they are much more likely to have Medicaid (40%) than the population overall (15%). Women with HIV are also significantly less likely than men to have private insurance.

When Kelly later lost her job, it took her two years to qualify for Social Security Disability Income (SSDI) — financial benefits for people who can’t work because of a disability, which people with AIDS often qualify for.

Throughout that process and to this day, Kelly’s Ryan White care manager has helped her navigate the financial aspects of her care.

In addition to costs, patients with HIV/AIDS face other barriers to getting the medications they need, including issues surrounding timing and availability, according to Dr. Aysha Khan, medical director of HealthIV, a specialty pharmacy and home infusion company.

Insurance hurdles such as prior authorization and step-therapy requirements that force patients to try less expensive medicines first can take weeks, delaying vital treatment. Insurers also typically require patients to get routine lab tests on a strict schedule to stay on a certain medication. If they miss the window, the approval process can start all over again. Khan said missing even one dose can put patients three steps behind.

To make matters worse, HIV/AIDS medications aren’t always readily available at a local pharmacy. They might only come from the manufacturer or certain specialty pharmacies.

“You can forget about getting a medication in an hour like you do at Walgreens or CVS,” Khan said.

Overcoming barriers

In addition to logistical barriers, many people with HIV/AIDS also face stigma, but people with HIV can find moral support online from other HIV/AIDS patients, in addition to tangible support from government agencies.

Along with online social networking forums for patients with specific conditions, nonprofit agencies such as The Well Project, provide online resources and community support for women with HIV/AIDS.

Numerous governmental and nonprofit resources also exist to help people with HIV/AIDS overcome tangible barriers to care, including the Ryan White Program. In addition to financial assistance, it covers home health and hospice; oral health services; substance use treatment; and nonmedical services such as housing, food, transportation and caregiver support.

The AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP), also part of Ryan White, gives funding to U.S. states and territories to pay for AIDS drugs for low-income people. Drug manufacturers may also help financially — many have programs to give patients free medications if they qualify based on income.

Reducing barriers to treatment can make HIV/AIDS a chronic condition rather than a death sentence. Kelly encourages other women with HIV/AIDS to adopt that mindset — and not to max out their credit cards like she did when she thought she was dying.

“I know you’re going to feel like it’s the end of the world, but it’s not,” Kelly said. “Live your life, take the meds, grab the bull by the horns.”