As told to Erica Rimlinger

From the time my periods started at age 12, they lasted more than a week, caused me to bleed through my clothes and doubled me over in pain. Even a prescription for the birth control pill at age 15 didn’t help my symptoms. As I got older, my periods got worse, but I thought this was just the price I paid for being a woman. I didn’t realize I was paying too much.

I joined the Army out of high school to get away from a difficult childhood in Abilene, Texas. After basic training, my test scores qualified me for a spot in the U.S. AMEDD Center and School’s nurse training program. Nursing, I found, fulfilled me as a person. I loved helping people and loved that I could do what I believed other providers often did not do: connect with people on a personal level and leave them in a better place than I found them.

But my menstrual suffering was costing me my career. Make no mistake: I was tough. I could wake up at 4 a.m. to run five miles with my platoon or work a physically demanding shift in a combat hospital. But when you are dry heaving in pain two weeks out of every month, the situation is unsustainable. I was repeatedly sent to the Troop Medical Clinic, or TMC, only to be given pain medication and a heating pad by the nurse practitioner or physician assistant. It never helped enough, and certainly didn’t provide a long-term solution. I faced a lot of skepticism, and more than once I was asked if I was really in as much pain as I said I was.

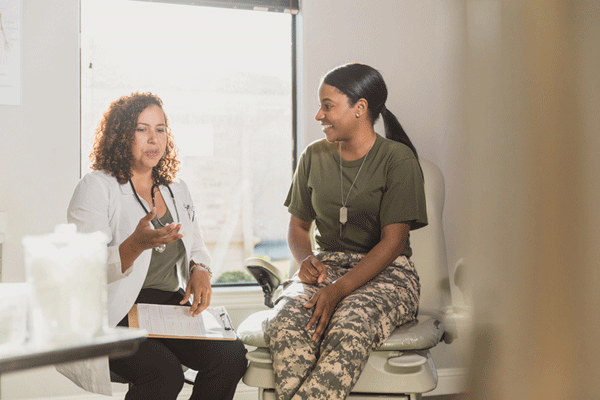

Finally, the Army gave me permission to see a gynecologist at the main hospital. I remember sitting ramrod straight in my uniform in the gynecologist’s office, learning that a barrage of imaging and laparoscopic testing confirmed I had endometriosis. My uterus was covered in adhesions, and my right ovary was embedded into the right wall of my uterus.

“What do we do now?” I asked, and was surprised again by the news that came next. At age 20, just eight years into my young womanhood, I’d be put into chemically induced menopause.

As my doctor explained my treatment plan, my mind plucked one statement out of the jumble of news: I probably wouldn’t be able to have children. I hadn’t even given thought to having children yet, and now, suddenly, that potential future was swept off the table before it had even formed in my mind.

Shortly after my first injections of the medication to stop my periods, I started having hot flashes. I was irritable and slept poorly. The side effects were so severe my doctor suggested I cycle on and off the medication: six weeks on, six weeks off. My periods returned, and this time they were so heavy I hemorrhaged clots and risked ruining my uniform every time I left the barracks. I also developed anemia. Endometriosis and I were an equal match for one another. But I was a tough young woman with an illness that was as relentless as my desire to prove my strength in its grip.

After a couple of years of toughing it out, my doctors came up with a plan C. “Let’s take your right ovary,” they suggested.

The procedure, called an oophorectomy, would leave me with one ovary. By this time, I was 22 and mentally exhausted. I weighed its loss against my quality of life and the strains on my career, especially the growing stress of having my superior officers not fully understand the extent of my illness. It seemed clear to me they thought I was either exaggerating my symptoms or that I was just not able to handle my “female problems.”

I decided to have the ovary removed, and for several months, experienced some real relief from my symptoms. So much so, in fact, I ended up getting pregnant against all the odds.

Four months after my daughter was born, a scope showed the lesions were back. I began a routine: I’d undergo surgery, it would help for a while, and then the lesions would redevelop. We tried chemical menopause a couple times again as well.

Through it all, I was a working mother. When I was assigned to travel to a 45-day training exercise in California, I realized how unlikely it was that I’d last 20 years in the Army. Because I had a young baby and was undergoing constant endometriosis treatments, I asked my superior officers if another nurse who was single and didn’t have endometriosis could swap with me to take this assignment. My request was denied, and I was sternly reminded that, “the Army did not issue” me my child, and “having monthly female issues” was my problem, not theirs.

This conversation stuck with me because, as the message was delivered down the chain of command, I realized not one person in the decision-making chain had a uterus.

I spent most of my 20s into my 30s dealing with life-disrupting periods, chronic pain and regular medical procedures while serving in the Army and raising my daughter before I got a medical retirement. Medical treatment in the civilian world offered me more choices and the opportunity to choose a healthcare practice that focused exclusively on women’s health. I never had that in the Army.

Some of my medical team members were great, like the OB-GYN who delivered my daughter. But I would have loved to have had more access while I was in the Army to doctors who practiced women’s healthcare. I also feel the Army could be more clear and upfront with servicewomen about how childbearing choices and reproductive issues can fit into a military career.

Most of all, I’d like all medical practitioners to trust women when they communicate what they’re experiencing. Our struggles are not always visible, but we know ourselves and our bodies best — and some of our toughest experiences are the ones male healthcare providers will never have to go through.