No one would blame you for assuming that the number of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) went down during the pandemic. After all, lockdowns prevented many of us from even talking to people outside our households — much less going out and having sex.

In fact, reported cases of STIs did go down during the early months of the pandemic in 2020, but they went back up by the end of the year. Combine this pandemic-related increase with the steady rise in STI cases that has been going on for seven years, and what do you get? A public health crisis.

What’s the difference between an STI and an STD?

You probably remember the term sexually transmitted disease (STD) from health class, right? While STD and STI are often used to mean the same thing, most public health experts now prefer the term STI. This is because a person can have an infection without knowing it, but only someone who is having symptoms can have a disease.

For example, a person can be infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) without ever getting sick with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). But they can still spread HIV to other people.

The hope is that focusing on infection rather than disease will help people understand that they can have — and spread — an STI without ever having a single symptom. Your infection may never turn into a disease, but you’re still contagious.

Why did STI numbers go up during the pandemic?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reported cases of gonorrhea went up 10% in 2020 compared to the previous year. Two types of adult syphilis went up 7% compared to 2019, while cases of syphilis in newborns (congenital syphilis, passed on from the mother) rose nearly 15% — a 235% increase from 2016.

While the number of chlamydia cases officially went down, the CDC says the decline is likely because fewer people were screened for (and diagnosed with) this STI during the pandemic, not because fewer people were infected.

One person who was not surprised by the pandemic-related rise in STIs is Oluwatosin Goje, M.D., an OB/GYN and reproductive infectious disease specialist at the Cleveland Clinic. Goje said that although she continued to see patients throughout the pandemic, she knew that many people put off routine healthcare — including STI screening and treatment — during this time.

“People were just trying to understand the pandemic and get through it,” Goje said. “They allowed some of their screening and testing to fall behind.”

Even if someone did want to see a healthcare provider (HCP) about an STI during the pandemic, many public health clinics were closed. Others remained open but had to shift their focus to Covid, Goje explained. This lack of access to care, combined with already-rising STI rates, creates the perfect storm.

Rising STI rates reflect inequalities

As for who is being affected by rising STI rates, certain groups of people appear to be more vulnerable. Looking at data from 2020, the CDC found that gay and bisexual men, young people and some ethnic and racial minorities are experiencing higher rates of STDs/STIs compared to the general population.

Sadly, this trend is not new — and it reflects longstanding issues around discrimination, lack of access to healthcare and other systematic inequalities. “The COVID-19 pandemic increased awareness of a reality we’ve long known about STDs,” said Leandro Mena, M.D., Director of the CDC’s Division of STD Prevention in a press release. “Social and economic factors — such as poverty and health insurance status — create barriers, increase health risks, and often result in worse health outcomes for some people.”

“If we are to make lasting progress against STDs in this country, we have to understand the systems that create inequities and work with partners to change them,” Mena added.

“There has to be early access to quality care — deploying appropriate tests and early and appropriate treatment — and we have to destigmatize STIs,” Goje said. “For example, for latent syphilis that we might see in pregnancy, they need three doses of medication every week. You don’t want to just get the first dose and then fall off the curve.”

A growing need for prevention and screening

If left untreated, STIs can take a serious toll on your health. This is particularly true for women, who may face infertility, pelvic inflammatory disease, cervical cancer and other complications after having an STI. Babies of infected mothers are at risk, too, since they can be born with an STI passed to them during pregnancy.

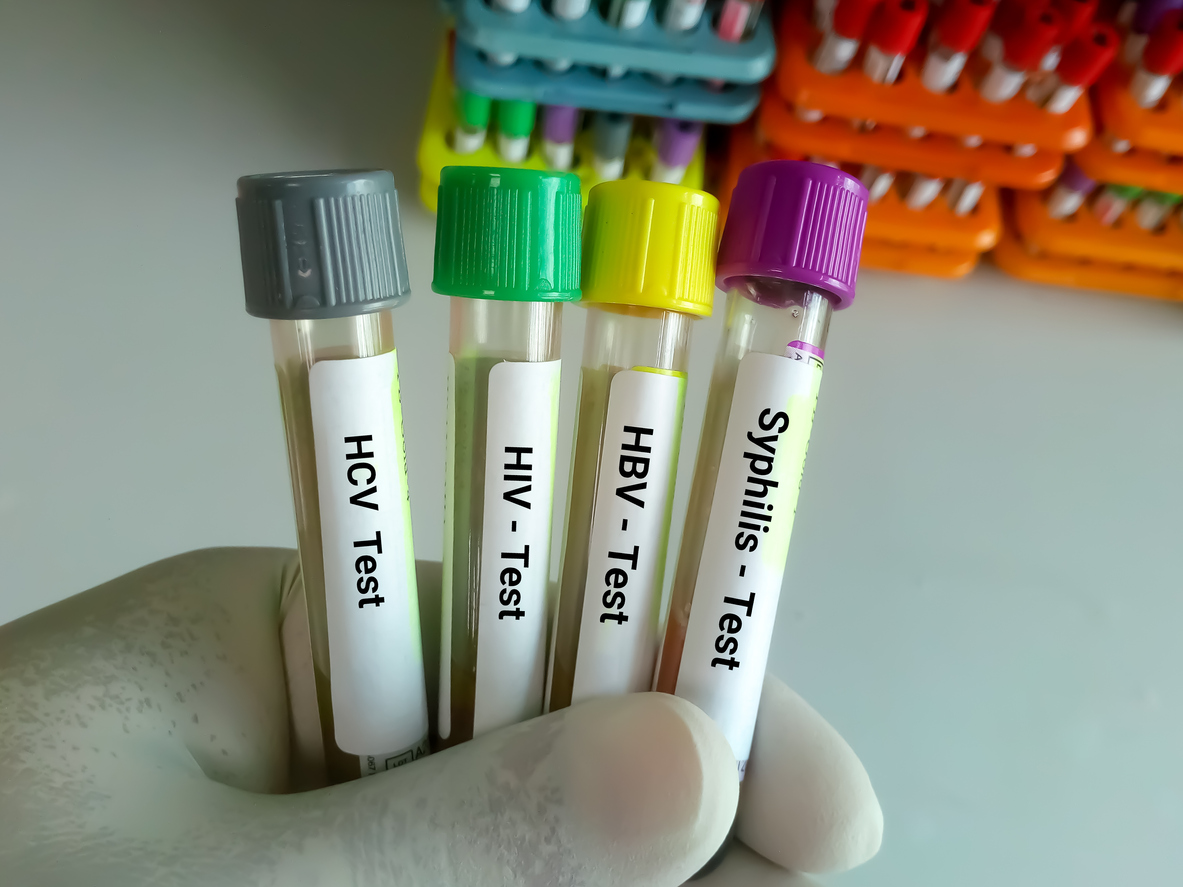

Some STIs — syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia and trichomoniasis — can be cured with medication. Others, including herpes, hepatitis B, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human papilloma virus (HPV) are viral infections that can’t be cured.

And even curable STIs are becoming harder to treat. Gonorrhea, for example, is becoming more and more resistant to the antibiotics used to cure it.

When it comes to preventing STIs such as HIV, gonorrhea, chlamydia and trichomoniasis, condoms work very well when used correctly. (It’s important to remember that condoms are the only method of birth control that protect against STIs.) Other prevention tools include vaccines for Hepatitis B and HPV and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), which is prescription medicine that reduces your chances of getting HIV from sex or injection drug use.

The sooner a person knows if they have an STI, the better their chances of avoiding long-term health problems — and the less likely they are to pass it on to others.

Since so many STIs don’t cause symptoms, it’s important to get screened regularly to make sure you’re infection-free. Screening guidelines vary according to the type of infection and other factors. Your HCP or a public healthcare worker can guide you through the screening process, or you can take this handy “Should I get tested for STDs?” quiz created by Planned Parenthood.

Where can you get tested for an STI?

You can get tested for an STI at your healthcare provider’s office. The CDC has created a resource that will tell you where to go for fast, free STI testing based on your ZIP code. You can also get tested for an STI at your healthcare provider’s office. And at-home STI testing is also an option in certain situations.

Read more about at-home STI testing.

Treating partners helps stop the spread of STIs

In addition to screening and testing, a prevention measure called expedited partner therapy (EPT) is being used to reduce STIs.

EPT means a provider can prescribe medication to treat gonorrhea, chlamydia and trichomoniasis to their patient and the patient’s sex partners without needing to see the partners.

It’s available without restrictions in 46 states and allowed under certain circumstances in Alabama, Kansas, Oklahoma and South Dakota.

EPT helps to break the chain of transmission by making it easy for a person exposed to an STI to get treatment without a clinic visit. “Think about my patient being treated,” Goje said. “If she goes back to the same partner that is not treated, she gets reinfected. If the partner has other partners, then they get infected. EPT is another tool in the toolbox to help reduce the spread of STIs.”

How can we end the stigma around STIs?

Screening and treatment aside, Goje believes ending the stigma around STIs is key to preventing them. “I’m hoping for a day where people talk about STIs the way we talk about high blood pressure,” Goje said.

Once you destigmatize STIs, Goje explained, a woman may feel more comfortable telling her provider she’s been exposed or asking to be tested. “Women need to be empowered to advocate for themselves.”