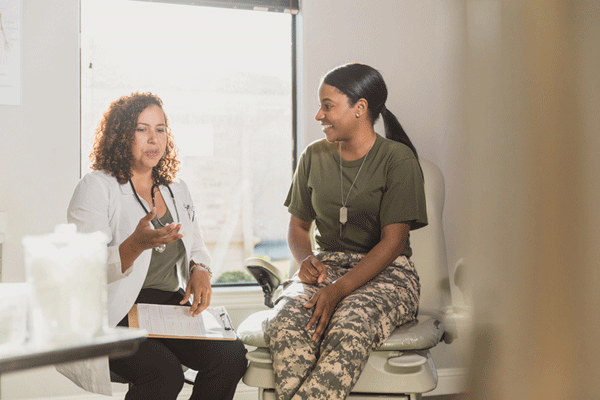

The Expert:

Shea O’Neill, M.D. is an Obstetrics & Gynecology Specialist based in San Diego, CA.

What is chronic pelvic pain?

Ultimately, chronic pelvic pain, to put a short answer to it, is the pelvic floor muscles are contracted and tight and they’re like cement. And so anything that hits them, moves them, touches them – a uterus, a bladder that’s full, stool moving through the intestine, an ovary that’s biologically active because it is an appendix, it just moves. Anything that touches that tight pelvic floor causes pain, and it’s the same thing, like somebody that has pain from clenching all the time. It’s a, it’s a musculoskeletal response that’s a very slowly evolving response. It does not happen in a week or a month.

What are examples of acute pelvic pain vs. chronic pelvic pain?

A really good definition of chronic pain is somebody with painful periods. That’s chronic. Classically, most doctors for for whatever reason, and most women, sadly, don’t think of it. They just think it’s part of being a woman: you have heavy painful periods. That’s just not true. So a chronic pain condition is heavy painful periods. So that’s one definition of a chronic pain condition. An acute pain condition would be, for instance, an ovarian cyst. Ovaries kind of make cysts, kind of like your skin makes freckles if you’re a light-skinned person. So ovaries make cysts. Many of them come and go. Many of them can be acutely painful, but acute pain, usually you can nail down really started at a very specific time, a very specific place. And, um, and so ovarian cysts can be an acute problem. Um, a pelvic infection can be an acute problem. Sometimes a kidney stone can be be pelvic pain. Um, a GI infection. So there’s anything that’s in the pelvis, um, the bladder, the intestines, the uterus, the vagina. Anything that’s in the pelvis, the back, the hips, that can be injured or affected, can cause an acute pelvic pain.

What are some causes of pelvic pain in servicewomen and service members with female biology?

Pelvic pain is sort of a chronic pain condition that’s actually an end result of lots of things, so it’s sort of a warning sign of a lot of different things that can be going on. Sort of like headaches are. If somebody has a headache, you know, we all sort of understand that something’s wrong. And so for chronic pelvic pain, it’s much the same way, so you have to really rule out what I like to call point-and-shoot things, sort of things that started Tuesday at two, and they’re very straightforward things. And it’s what most, you know, providers on a variety of levels can take care of, and then the chronic pain is more of a long-term issue, and sometimes you can have an acute issue on top of a chronic issue, which is probably the more complicated one. So there’s a large, large list of things that can cause both acute and chronic pelvic pain.

Is endometriosis a common cause of pelvic pain? What are the symptoms?

Endometriosis is commonly seen in people with pelvic pain, so I should probably say so. People with pelvic pain, 70% of them have endometriosis, but everybody with endometriosis does not have chronic pelvic pain. So endometriosis is a chronic pain syndrome and it it sort of works on on a continuum. The classic story is that they, a woman, starts out with heavy painful periods at the time of her first cycle, and then it turns into pain outside of her cycle, and then it turns into pain every single day, and sort of the final, classic symptom is pain with intercourse. Um, so there’s a spectrum that people can be on, and if they start right at the time of their first period, hopefully somebody has intervened and moved towards the most common way to manage it, which is hormonal suppression. Suppressing the cycle is sort of the ultimate key to managing endometriosis, but endometriosis, the way I look at it, is a chronic pain condition, kind of like getting migraines in your teen years or having chronic low back pain or chronic constipation, so endometriosis can be classified as a chronic pain condition.

What is the treatment for endometriosis?

The treatment for endometriosis is cycle suppression. It’s really simple and we can suppress our cycle with hormones, we can suppress it, um, later on in life, and if they’re close to menopause, certainly Lupron or surgery, but cycle suppression is how you treat endometriosis.

Is pain during sex normal?

Pain with intercourse is probably more important than pelvic pain. Um, I think that people don’t come and talk about pain they’re having with intercourse until their relationships are are on such a teetering edge, but they’ll deal with pain for a long time. So so by the time I see someone with pelvic pain, it’s very unusual if they don’t have pain with intercourse, but they feel like they have a socially acceptable reason to make an appointment. So people people who have pelvic pain but don’t have pain with intercourse, or just early on, then they’re lucky that they’ve come in sooner than later. But more often not, what’s really driving people is they’re having pain with intercourse and they thought it was normal, just like they thought it was normal to have pain with your periods. I’m like, no, it’s not, it’s not, so if you’re having pain, it’s a problem. So pain with intercourse can be treated, um, and so it’s treated exactly the same way chronic pelvic pain is. Let’s figure out all the things that are wrong. Let’s get you into physical therapy. Let’s get you straightforward medications that primary care can take care of. Let’s manage your headaches. Let’s, um, rehabilitate your pelvis, and let’s give you a different way to manage your stress other than stuffing your feelings in your pelvis. Um, and that’s what causes pain with intercourse.

When should someone see their healthcare provider for pelvic pain?

I would say they should see their healthcare provider anytime they have any pain. Commonly, they finally come in to be evaluated for pelvic pain when something in their life is being disrupted. For instance, if they have pain with intercourse, then their relationship is being disrupted. If they have pain that prevents them from completing their, um, very physical duties, they come in for evaluation. But it’s very unusual that the pain started a month ago. They’ve been dealing with the pain for a long time and they’ve mustered through it and finally, all of their self-adaptive techniques are worn out. So I would encourage them to come in sooner than later, but I think that’s a human, um, I guess response and also a military response to sort of push through it. So anybody should come in when they have any kind of pain. Pain is a signal that something’s wrong, and so if you have recurrent pain, you should come in.

What advice do you have for a service member who might need a second opinion or a specialist because their provider isn’t experienced with pelvic pain?

Servicewomen and service, people, and I’m going to actually extend this to people, commonly don’t have providers that are well-versed in pain. They commonly don’t have providers that are well-versed in chronic pain. And so women have more chronic pain than men. So you can sort of sub-categorize this, but I guess it goes back to what I said earlier. Pain is a signal that something’s wrong, so if you feel like somebody has done a workup with … The the most common response is, you must have missed something, and I try to educate people that no, they probably didn’t miss anything. That doesn’t mean you’re not in pain. Now you’re going to have to address it in probably a longer appointment, um, and continue to advocate for yourself that something is wrong. I understand it’s not the straightforward things that can cause acute pain, but something’s wrong. So asking for a second opinion sometimes can be difficult. Um, I, sometimes in the military, they have a very hierarchical way of dealing with things. It depends on their deployments. It depends on, um, sort of mission-critical issues. So if there are mission-critical issues, um, then they they may or may not have the luxury of a second opinion. But mission-critical issues are never long-term, so they can always look for that when they are finished with whatever critical issues there are. They there are several levels of ancillary health providers in the military, so they may go to their independent duty corpsman. They may go to their physician assistant. They may have a nurse practitioner, a nurse midwife, and then finally an OB-GYN or a primary care doc or a flight doc. There’s so many people they could go to, but they are always able to ask for a second opinion. That’s kind of all they need to remember. They still have that right. Anybody receiving healthcare has a right to get another opinion about what’s going on, or to perhaps see somebody in a different specialty. So it’s more about reassuring people they can advocate for themselves, and if something’s wrong, and they think something’s wrong, they need to just ask for someone else with, you know, new eyes.

What can a service member expect from a medical appointment?

Evaluating chronic pain is not done by many people, to be quite honest. Um, so I can’t really give them what to expect. It’s much easier to tell them what to expect when they’re having an acute issue. When they’re having a chronic issue, um, it probably takes probably more classic approaches. They would see their primary care person. Um, and they would have to feel like that primary care person is listening to them. And if that primary care person is listening to them, I wouldn’t expect much in the first visit or two. I would expect perhaps one or two things to be ruled out each time. Most people with chronic pain are very patient and have no problem with that. They really just don’t want to feel brushed off, so if they feel, they’re not being listened to or something’s being missed, that’s where advocating for yourself comes in. But also, um, allowing the provider they’re seeing to say, all we can handle today is this, um, then we’ll move on to that. And sometimes if patients walk in with, I understand I have a lot going on, but my more pressing issue is this and this, there’s usually never just one thing, because then if they had one thing wrong, they would expect that one thing to be looked at. But as I said, chronic chronic pelvic pain is the end result to many things that have come before, and sadly, the patients are usually at their wit’s end, and so they’re trying to give a very long history in five minutes.

Why is it sometimes difficult to get a diagnosis for a pelvic pain condition?

The most important thing they need to understand is, I would say, 99% of providers, what their main goal is to make sure that what’s wrong with you is not going to kill you or isn’t a cancer. Sort of, that’s our training, is to make sure it’s not the most extreme and the most awful of diagnoses. And so, when we are saying, well, we don’t see anything wrong, what the patient hears is that, they’re they’re, what do you mean you don’t see anything? But I’m in pain. And we’re not very good at saying, so, I’m gonna see you next time because we need to figure out why this is hurting. So their expectations are to be ruled out for something dangerous. That’s an expectation, but once that happens, um, they’re going to need to assume it’s not dangerous and really advocate for themselves for some validation, that I understand that I don’t have chronic appendicitis, but I still have this pain down here and I’d really like to know what it might be and what steps I can take to figure that out.

Can you speak to the stigma associated with pelvic pain?

Doctors, um, providers in general, we are not trained on chronic pelvic pain, or really chronic pain conditions. We’re really trained on point and shoot, so a lot of chronic pain conditions, essentially, after of course, lesions are ruled out, something that has an actual cause and effect, a lot of chronic pain conditions actually have a root in a traumatic event in this person’s life. And because they have a trauma-informed, response to anything that happens to them, both physically and emotionally, sadly, what gets attributed to pelvic pain is a history of sexual trauma, and so that’s the stigma. Not necessarily because it’s a male-dominated profession, but I promise you plenty of female providers make an assumption of somebody’s chronic pelvic pain – they’ve been sexually traumatized.

How can servicewomen and service members with female biology overcome pelvic pain stigma?

I again, this is kind of, I I think it’s going to be a hard thing to not to avoid, because it’s on our end. It’s not on the patient’s end, so the stigma has more to do with we don’t know what to do with you, so we’re going to project that onto you. That’s the stigma, um, but but I’ve, you know, been working for a long time trying to educate providers and kind of flip things because chronic pain patients in general are the easiest patients in in my practice to deal with. They’re very straightforward. There’s no secondary gain, and they they really are fairly textbook, which can frustrate a lot of pain patients by the time they come see somebody who deals with chronic pain because they’re like, I don’t I don’t understand why nobody put this together. Well, we don’t put it together because we usually have 10 minutes with you and we don’t have 10 minutes with an automatic follow-up appointment and an automatic follow-up appointment. So we have 10 minutes with you that took you four months to get in. Now, it’s going to be another four months before we see you. So there’s so many things really wrong with this system. I don’t think it’s male dominated. I think it’s provider dominated.

What would you tell your best friend if they were struggling with pelvic pain?

I tell them pain means something’s wrong. You need to go advocate for yourself and you need to go be seen. And you need to try to find a pain specialist in the area, not an anesthesia pain specialist, but an OB-GYN pain specialist. Or, just ask your primary care doctor to get you into therapy, suppress your cycle, and you know, perhaps we talk about what might be causing it. So I just, I tell my friends and family and children and their friends the same thing I tell all patients. Um, I don’t treat them any differently. So pain means something’s wrong, and pain with intercourse is not normal.

Experta:

Shea O’Neill, M.D.

Especialista en obstetricia y ginecología con consultorio en San Diego, CA

¿Qué es el dolor pélvico

En definitiva, el dolor pélvico crónico, para dar una respuesta corta, se produce porque los músculos del suelo pélvico se contraen y se aprietan como si fuesen cemento. Y, por eso, cualquier cosa con la que tienen contacto, que los mueve, que los toca, ya sea un útero, una vejiga llena, excremento que se mueve a través del intestino, un ovario biológicamente activo porque es un apéndice, simplemente se mueve. Cualquier cosa que toca el suelo pélvico contraído causa dolor y es como si fuese una persona que tiene dolor por apretar los músculos todo el tiempo. Es una reacción musculoesquelética con una reacción que evoluciona muy lentamente. No sucede en una semana o un mes.

¿Cuáles son algunos ejemplo de dolor pélvico agudo vs. crónico?

Una muy buena definición de dolor crónico es alguien con periodos menstruales dolorosos. Eso es crónico. Tradicionalmente, la mayoría de doctores, por algún motivo, y la mayoría de mujeres, desafortunadamente, no piensan en eso. Solo asumen que es parte de ser mujer: tener períodos menstruales abundantes y dolorosos. Eso simplemente no es verdad. Períodos menstruales abundantes y dolorosos es una condición de dolor crónico. Es una definición de una condición de dolor crónico. Una condición de dolor agudo sería, por ejemplo, un quiste ovárico. Los ovarios hacen quistes, tal como cuando tu piel hace pecas si tienes piel clara. Así mismo, los ovarios hacen quistes. Muchos de ellos van y vienen. Muchos de ellos pueden causar dolor agudo, pero usualmente puedes indicar precisamente el momento en que empieza un dolor agudo, en un lugar específico. Por eso, los quistes ováricos pueden causar un dolor agudo. Una infección pélvica puede causar un dolor agudo. A veces un cálculo renal puede causar un dolor agudo. Una infección gastrointestinal. Así que cualquier cosa que se encuentre en la pelvis, la vejiga, los intestinos, el útero, la vagina. Cualquier cosa que se encuentre en la pelvis, la espalda, la cadera, cualquier cosa que pueda lesionarse o verse afectada, puede causar un dolor pélvico agudo.

¿Cuáles son algunas causas de dolor pélvico de las mujeres militares y de miembors de las fuerzas armadas con biología femenina?

El dolor pélvico es parecido a una condición de dolor crónico y de hecho, ese es un resultado final de muchas cosas, es como una señal de advertencia de muchas cosas que pueden estar pasando. Tal como los dolores de cabeza. Si alguien tiene un dolor de cabeza, todos entendemos que algo está mal. Para el dolor pélvico crónico, eso también aplica mucho, así que tienes que descartar lo que llamo cosas que puedes identificar y solucionar, tales como cosas que empezaron el martes a las dos y son muy simples. Y eso es lo que la mayoría de proveedores de servicios médicos a varios niveles pueden solucionar, pero el dolor crónico es un problema más a largo plazo y a veces puedes tener un problema de dolor agudo además de uno de dolor crónico, lo cual es probablemente lo más complicado. Por eso, hay una lista muy larga de cosas que pueden causar dolor pélvico agudo y crónico.

¿Es la endometriosis una causa frecuente de deolor pélvico? ¿Cuáles son los síntomas?

La endometriosis comúnmente se observa en personas con dolor pélvico, así que probablemente diría eso. El 70% de personas con dolor pélvico tienen endometriosis, pero no todas las personas con endometriosis tienen dolor pélvico crónico. Por eso, la endometriosis es un síndrome de dolor crónico y su evolución es más o menos continua. La historia clásica es que una mujer empieza con períodos menstruales abundantes y dolorosos inicialmente durante el período, luego fuera de su período menstrual y luego se transforma en dolor todos los días, y finalmente, el síntoma clásico es dolor durante las relaciones sexuales. Hay un espectro de situaciones en las cuales las personas pueden encontrarse y si abordan el problema inmediatamente cuando el dolor ocurre inicialmente solo durante el período menstrual, con algo de suerte alguien ya habrá intervenido y habrá implementado la forma más común de manejarlo, la cual es la supresión hormonal. Suprimir el período menstrual es, en general, el mejor método para manejar la endometriosis, pero, en mi opinión, la endometriosis es una condición de dolor crónico, es como tener migrañas en la adolescencia o como dolor crónico en la parte inferior de la espalda o estreñimiento crónico, por lo que la endometriosis puede clasificarse como una condición de dolor crónico.

¿Cuál es el tratamiento para endometriosis?

El tratamiento para la endometriosis es la supresión de los períodos menstruales. Es muy simple y podemos suprimir nuestros períodos menstruales con hormonas, podemos hacerlo en etapas posteriores de nuestras vidas y si tienen edades que se acerquen a la menopausia, ciertamente Lupron o cirugías son unas opciones, pero la supresión de los períodos menstruales es el tratamiento para la endometriosis.

¿Es el dolor durante relaciones sexuales algo normal?

El dolor durante las relaciones sexuales es probablemente más importante que el dolor pélvico. Creo que las personas no hablan acerca del dolor que tienen durante relaciones sexuales hasta que sus relaciones están al borde de tambalear, pero harán tenido dolor durante mucho tiempo. Por eso, para cuando examino a alguien con dolor pélvico, es muy inusual que no tenga dolor durante las relaciones sexuales, pero siente que tiene una razón socialmente aceptable para agendar la cita médica. Por eso, las personas que tienen dolor pélvico, pero no tienen dolor durante las relaciones sexuales, o que vienen pronto, tienen suerte por venir pronto en vez de después. Pero más a menudo, lo que realmente incentiva a las personas es sentir dolor durante las relaciones sexuales pensando que es algo normal, tal como piensan que es normal tener dolor durante los períodos menstruales. Les digo que no lo es, si sientes dolor, eso es un problema. El dolor durante las relaciones sexuales puede tratarse, se trata igual que el dolor pélvico crónico. Identificaremos todas las cosas que están mal. Te proporcionaremos terapia física. Te daremos medicamentos sencillos que tu doctor de cabecera puede prescribir. Trataremos tus dolores de cabeza. Rehabilitaremos tu pelvis y te proporcionaremos otras formas en las que puedes manejar tu estrés en vez de que tu pelvis sufra las consecuencias. Y eso es lo que causa el dolor durante las relaciones sexuales.

¿En qué momento deberían las personas visitar a sus proveedores de servicios médicos por dolor pélvico?

Pienso que deberías visitar a tu proveedor de servicios médicos en cualquier momento que sientas dolor. Frecuentemente, vienen finalmente a que las examine por dolor pélvico cuando algo en sus vidas se ha alterado. Por ejemplo, si alguien siente dolor durante las relaciones sexuales, y su relación está viéndose afectada. Si sienten dolor que evita que realicen sus actividades físicas, vienen a que las examine. Pero es muy inusual que el dolor haya empezado hace un mes. Han estado lidiando con el dolor durante mucho tiempo y finalmente, todas sus técnicas de adaptación se han agotado. Así que las motivaría a que vengan pronto en vez de después, pero pienso que esa es la naturaleza humana, supongo que es una reacción de la gente en general y de los militares, el tratar de afrontarlo. Por eso, las personas deberían venir si tienen cualquier tipo de dolor. El dolor es una señal de que algo está mal, por lo que si tienes dolor recurrente, deberías venir.

¿Qué consejo tienes para un miembro de las fuerzas armadas que necesita una segunda opinión o un especialista porque su proveedor de servicios médicos no tiene experiencia con dolor pélvico?

Las mujeres militares y, creo que voy a extender esto a las personas en general, frecuentemente no tienen proveedores de servicios médicos que tengan un conocimiento adecuado en lo que se refiere al manejo del dolor. Frecuentemente no tienen proveedores de servicios médicos que tengan conocimiento adecuado en lo que se refiere al manejo del dolor crónico. Y por eso las mujeres tienen más dolor crónico que los hombres. Así que esto puede subcategorizarse, pero supongo que lo que dije anteriormente aplica para esto también. El dolor es una señal de que algo está mal, así que si sientes que alguien ha preparado… La respuesta más frecuente es, probablemente no te diste cuenta de algo y trató de educar a la gente que no, probablemente no es que no se dieron cuenta de algo. Eso no significa que no sientas dolor. Ahora tendrás que tratarlo probablemente en una cita médica más larga, y debes seguir defendiendo tus derechos porque algo está mal. Entiendo que no son las cosas simples las que pueden causar dolor agudo, pero algo está mal. Pedir una segunda opinión a veces puede ser difícil. Y a veces en las fuerzas armadas, tienen una forma muy jerárquica de hacer las cosas. Depende de sus despliegues militares. Depende de los asuntos críticos de la misión. Así que si hay asuntos críticos de la misión, puede que no tengan la posibilidad de una segunda opinión. Pero los asuntos críticos de la misión nunca son a largo plazo, así que siempre pueden buscar eso cuando los asuntos críticos ya no apliquen. Existen varios niveles de proveedores de servicios médicos auxiliares en las fuerzas armadas, por lo que pueden acudir a su ayudante médico independiente de turno. Pueden acudir a su asistente médico. Pueden acudir a una enfermera certificada, a una enfermera partera, a un ginecólogo obstetra, al doctor de cabecera o a un doctor en el avión. Hay tantas personas a las que pueden acudir y siempre podrán pedir una segunda opinión. Eso, básicamente, es todo lo que deben recordar. Todavía tienen ese derecho. Cualquier persona que reciba atención médica tiene derecho a obtener otra opinión sobre lo que está pasando, o talvez tener una consulta con un médico con otra especialización. Lo más importante es asegurar a las personas que pueden defender sus derechos y que si piensan que algo está mal solo tienen que pedir a otra persona que los vuelvan examinar.

¿Que puede esperar un miembro de las fuerzas armadas de una cita médica?

La evaluación de dolor crónico no se hace por muchas personas, para ser honesta. Así que no puedo decirles que deben esperar. Es mucho más fácil decirles que esperar si tienen un problema de dolor agudo. Si tienen un problema de dolor crónico, probablemente se implementarán métodos más tradicionales. Tendrán una consulta con su proveedor de servicios médicos de cabecera. Y tienen que sentir que el proveedor de servicios médicos de cabecera les escucha. Y si ese proveedor de servicios médicos de cabecera les escucha, no esperaría mucho en la primera o en las dos primeras consultas. Esperaría tal vez que una o dos cosas se descarten a la vez. La mayoría de personas con dolores crónicos son muy pacientes y no tienen ningún problema con eso. Solo no quieren que las ignoren, así que si sienten que no les escuchan o que algo se ignora, ahí es cuando deben defender sus derechos. Pero, también deben permitir que el proveedor de servicios médicos con el que tienen la consulta diga que todo lo que pueden hacer hoy es esto, Y que entonces hagan eso. Y a veces, si los pacientes entran diciendo entiendo que me pasan muchas cosas, pero mi problema más grave es esto y esto, normalmente no solo es una cosa, porque si tuviesen solo una cosa que anda mal, esperarían que eso se evalúe. Pero tal como dije anteriormente, el dolor pélvico crónico es el resultado final de muchas cosas que han pasado antes, y desafortunadamente, las pacientes están haciendo su último esfuerzo, por lo que tratan de proporcionar un historial muy largo en cinco minutos.

¿Por qué a veces es difícil recibir un diagnóstico de una condición de dolor pélvico?

Lo más importante que deben entender es que para el 99% de los proveedores de servicios médicos, su meta principal es asegurarse de que el problema que tengas no te mate o no sea cáncer. Este es nuestro entrenamiento, es asegurarnos de que no se trate de los diagnósticos más extremos y terribles. Por eso, cuando decimos, bueno, no vemos nada mal, Los pacientes nos dicen, ¿a qué te refieres con que no ves nada? Pero siento dolor. Y no somos muy buenos cuando decimos “tienes que venir a otra cita porque debemos determinar qué es lo que te duele”. Así que debe descartarse de sus expectativas algo peligroso. Esa es una expectativa, pero una vez que eso sucede, deben asumir que eso no es peligroso y deben defender sus derechos para obtener una validación, para que entiendan que no tienen una apendicitis crónica, pero todavía tienen ese dolor allí y que les gustaría saber qué podría ser y qué pasos necesitan tomar para averiguarlo.

¿Puedes hablar del estigma asociado con el dolor pélvico?

Los doctores, es decir, los proveedores de servicios médicos, en general, no recibimos entrenamiento para el dolor pélvico crónico, o en general para condiciones de dolor crónico. Realmente nos entrenan para cosas que pueden indicarse y solucionarse, por lo que muchas condiciones de dolor crónico, esencialmente, desde luego, después de descartar lesiones, cosas que tienen una causa y efecto más tangibles, muchas condiciones de dolor crónico de hecho tienen su origen en algún acontecimiento traumático de la vida de esta persona. Y puesto que tienen una reacción informada a eventos traumáticos en lo que se refiere a cualquier cosa que les pasa, física y emocionalmente, desafortunadamente, lo que se atribuye al dolor pélvico son antecedentes de traumas sexuales y ese es el estigma. No necesariamente porque sea una profesión en la que proliferan los hombres porque les aseguro que muchas proveedoras de servicios médicos asumen que el origen del dolor pélvico crónico de alguien se debe a traumas sexuales.

¿En qué forma pueden las mujeres militares y miembros de las fuerzas armadas con biología femenina superar el estigma del dolor pélvico?

Esto puede ser algo difícil de evitar porque depende de nosotros. No depende de la paciente, así que el estigma probablemente se debe a que no sabemos que hacer contigo, así que lo vamos a proyectar a ti. Eso es un estigma, pero he estado trabajando durante mucho tiempo, tratando de educar a proveedores de servicios médicos para cambiar esto porque los pacientes con dolor crónico, en general, son los más fáciles que puedes manejar. Son muy honestos. No hay metas secundarias y la mayoría de sus casos se describen en la literatura, lo cual puede frustrar a muchos pacientes con dolor porque para cuando tienen consultas con alguien que maneja dolor crónico, dicen, no entiendo porque nadie más pudo identificar esto. Bueno, no lo identificamos porque usualmente solo tenemos 10 minutos contigo y no tenemos 10 minutos con una cita automática de seguimiento. Es decir, tenemos 10 minutos contigo los cuales tuviste que agendar con cuatro meses de anticipación. Ahora, pasarán otros cuatro meses antes de que te veamos nuevamente. Hay muchas cosas que están muy mal con este sistema. No pienso que sea una industria dominada por los hombres. Pienso que es dominada por los proveedores de servicios médicos.

¿Qué dirías a tu mejor amiga si tuviese dificultades asociadas con dolor pélvico?

Les digo que el dolor indica que algo está mal. Debes defender tus derechos y debes hacer que te examinen. Y debes tratar de encontrar un especialista en dolor en el área, no un especialista de anestesia para el dolor, sino un especialista de dolor ginecológico obstetra. O solo pide a tu doctor de cabecera que te proporcione alguna terapia, que suprima tus períodos menstruales y talvez hablemos acerca de lo que podría estar causándolo. Así que, solo digo a mis amigos, familiares, a mis hijos y a sus amigos lo mismo que digo a todas mis pacientes No los trato en una forma diferente. El dolor significa que algo está mal y tener dolor durante las relaciones sexuales no es algo normal.